When I lived in Cambridge, I had seven large wooden bookcases, stuffed with books.

Mostly philosophy, literature, mythology, poetry, and world religions. And art books. Oversized, gorgeous, collector’s editions. Some I picked up at museums — I had publications from American and European museums — and others I bought simply because I couldn’t resist their beauty.

Some of my favorites were on the Uffizi, Van Gogh, The Louvre, Kandinsky, Leonardo. And Giotto. I loved the volume on Giotto, a magnificent publication that received glowing reviews, for it celebrated the father of the Italian Renaissance in remarkably accurate, color saturated reproductions. The oversized edition had sumptuous fold out plates, and detailed images in which you could see the master’s brush strokes, dabbles, accents, photographic close-ups whose beauty brought me to tears.

When I left Cambridge, in the whirlwind of change and dissolution, I sold or gave away most of my books. I didn’t mind getting rid of my other stuff, but getting rid of the books was something I never imagined I would do.

I remember crying to a friend in the middle of my bankruptcy, pending eviction, moving to the middle of nowhere chaos, “other women have children, and homes, and whatever it is that those women have. I have my books, they represent my life, and I have to get rid of them.” I was blathering as though I had been given a diagnosis of terminal cancer with only weeks left to live.

My victim narrative was in overdrive, my books tethered to something that needed to be excised at the root level.

I can’t tell you how much it pains me to write that, now. How transparently silly and self-indulgent I was being. But as I spoke those words to him, I started realizing that is why the books had to go. I was too heavily invested in an identity that wasn’t working, and I needed to let go so that I could dive into deeper creative waters. I also needed to embrace parts of myself that I had too long-buried, under work and study and self-loathing.

I didn’t know it then. But I do, now.

Getting rid of the books was transformative, because it meant letting go of one identity to embrace another, and I began understanding that all of this dissolution was the destruction before an inevitable creative resurrection. My choices, however radical they may seem on the surface, were an affirmation that I was willing to do what needed to be done to get to where I wanted to go. Which is what I have always done, with a kind of unflinching resolve when my back is against the wall. Ironically, where I wanted to go was exactly why I had all the books: I wanted a bold, creative, meaningful life, full of a spiritual, emotional, and intellectual richness.

“She who would find her life must lose it.”

I was getting rid of the unnecessary to get the meaning that I sought. The books were central to my intellectual search for meaning. But I needed to shift my perception. I was beginning an exploration in which I crafted meaning from the inside out, not the outside in.

For this reason, although I didn’t understand why, once I started getting rid of the books, they couldn’t go fast enough. I packed them up into suitcases, called a cab, loaded the cab with the suitcases, which I then hauled down to the basement of Harvard Bookstore, that is, their used book buying department. Sometimes someone offered to help me get them down the stairs. Sometimes I was on my own lugging a hundred pounds of books down to the basement. Trip after trip after trip, it took several trips a day for days to carry out the heroic task.

I won’t say that it doesn’t still sometimes pain me to realize the tens of thousands of dollars of books that were swept from my life in a matter of days. Other women have children and homes and cars and whatever it is that they have. I had books. And I had an extraordinary library. As I went through my life’s exhaustive hoarding, I appreciated what great taste I had, the breadth and scope and intelligence that I managed to stuff into my collection. Some of civilization’s finest written works, lovingly sitting on my shelves, row by row by row.

I also had a fairly extensive collection of Folio editions, beautifully bound and illustrated classics, that lined several shelves like the kings and queens of the collection. No used books on those shelves, just classics elegantly bound and sitting in embellished slip cases, looking grand and stately.

It was a library that I would have coveted. I had made it mine.

The art books were the last to go, sold to the book store just days before my move. While everything else in my life I let slip through my fingers with relative ease, the art books were precious, for they represented my life’s treasured adventures. They represented not just beauty for its own sake, but visits to some the world’s great museums, that I had managed to tuck into visits here and there. There was a gorgeous, red slip cased, double volume on Van Gogh that I shipped to myself from The Louvre. The complete catalog of Camille Claudel, bought at the Musée Rodin. Catalogs from exhibits that I made the time to visit, Kandinsky, Picasso, Brancusi.

The search for meaning lay most conspicuously in the art books. Travel, adventure, beauty, spiritual longing, stored in two shelves of gorgeous books that circumstance dictate that I leave behind.

It took three cab trips of several suitcases, but they were gone in one day.

The several hundred dollars helped pay for my move.

****

I don’t have room for books, now, though I have managed to collect a couple of stacks in the art supply littered living area. I ask for a lot of interlibrary loans from our small community library, and I sometimes access the New Hampshire public library’s online system of electronic content.

Our library is right down the road from me. Out my front door, over the river’s bridge, down the road a couple of hundred feet. Our librarian is incredibly helpful, always making sure I get my idiosyncratic requests from larger libraries. She once even went to the trouble of borrowing from a New Hampshire university, though they were somewhat begrudging in filling the request.

The pubic library here is funded mostly through community efforts. This weekend there were bake sales and book sales through the “Friends of the Library.” These events coincided with Old Home Week, a rural fair celebrating the old historical homes in this area. The weekend draws a lot of tourists — there’s a large craft fair held in the elementary school, the library has several events, and both our community store and our library generate a large chunk of their annual income from Old Home Week’s visitors.

I normally don’t attend bake sales or community book sales. I rarely eat sweet baked goods, and I usually doubt that any of the books will be to my liking. But something told me to go to the book sale. I just knew to go. I walked down the street to the library, and on the front lawn stood a large white awning, covering the bake sale and rows and rows of boxes of books. Three smiling women volunteers greeted me. Most of the boxes were of contemporary best-selling fiction, which isn’t my interest.

“Do you have anything that is pretty and colorful, maybe some photography books?” I asked, thinking of my art journals.

“Nonfiction,” the volunteer said, “is in the library, downstairs.”

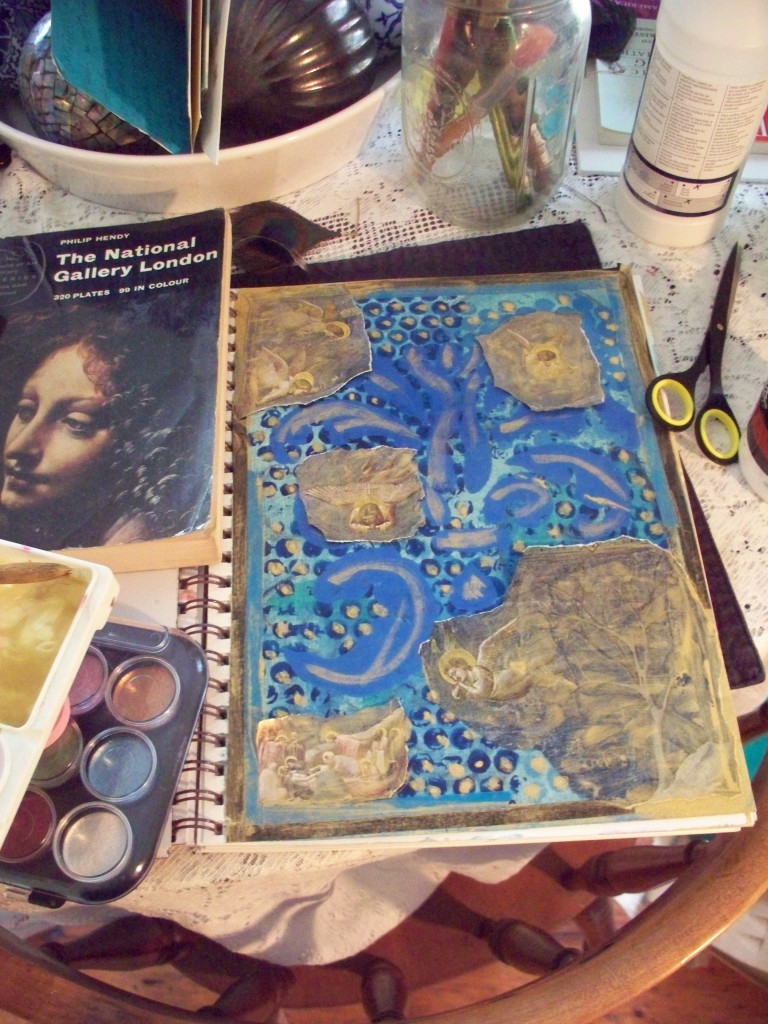

I walked in, and at the top of the stairs were two boxes of books. On the top of one box was a book bearing Leonardo’s famous angel from “The Virgin Of The Rocks.” The angel got my attention, immediately. I started digging in the box, and there were old art history books. Varying degrees of quality, but lots of books with color plates. Color plates for art journals. I was ecstatic. A book on Giotto. A book on works in The National Gallery. A book on Leonardo. A large color book on the Uffizi. A beautiful small book on The Louvre collections.

“Hey, are these for sale,” I asked.

“No. Those aren’t for sale.”

My heart sank.

“Oh, wait. One box isn’t. Let me look at the other box.” Our librarian walked over. “Yes, the books in that box are for sale.”

I dove in with abandon, “Oh my goddessess,” I sang outloud. Book after book contained plates that could be used in my art journals, a luxury I never would have allowed myself with my other art books, but here they were sitting and waiting for me at the top of the stairs.

Waiting for me, in this box, not even shelved with the other book sale books. Art for my creativity. Not art to sit on a shelf, but images I could use to develop my own voice, my own creativity.

I dug in deeper. “How To Draw A Horse” found its way into my fingers, complete with illustrations and sketching instructions. I smiled from a place of quiet if ebullient joy. “The Year Of The Horse,” my year. My promise of creative adventure. (Search for “The Year Of The Horse,” if interested in reading the backstory. The book was nothing less than Providential.)

There’s a time for simplicity. Then there’s a time to go all in. This was a moment to go all in. Restraint wasn’t called for, this was a time for Blakean excess. “The road of excess,” wrote Blake, “leads to the palace of wisdom.”

All in.

Two large stacks of exploitable art books made their way into my grateful arms, for twenty dollars.

******

I awoke last night drafting this essay in my sleep, going in and out of dreams, remembering my life as it was less than two years ago. For it was about this time in 2012, that I was hauling books to Harvard Book Store, selling my futon and bookcases, giving away porch loads of stuff to The Salvation Army, having no clue about where my life was going. Leaping into the unknown, yet again, with a vague idea of becoming a writer, as though it wasn’t something I didn’t already do, all of the time.

I thought of my beloved art books, and my treasured library. I will have a library again, larger and even more voluptuous in its excesses, I believe. But now is not that time. Now is the time for embracing my voice, with clarity and conviction, and writing about why it was important to abandon other people’s ideas to craft my own.

Perhaps most important, I know with certainty, not the certainty that blinds you, but the knowing that’s been earned from living one extraordinary experience after another, and learning to listen a little better to that inner voice, that there’s always another side to our darkest days, if we let life slip easily through our fingers.

We can get better at it. We may never arrive, but a life well lived means letting life flow through you, instead of reaching for it over and over, grabbing onto something as permanent, then getting upset when it slips through your fingers, as all of life does.

“Other women have . . .” such a powerful reflection of where I was and who I thought myself to be.

Last week, I returned some books at the library, and entered a raffle to support the summer reading program. The volunteer said to me, “Well, if you’re lucky, you will win.”

“I’m one of the luckiest people I know,” I said, with an understanding of how many in the world would look at my life and say “blessed.”

“Well, you’ve made good decisions.”

Yes, I have. And no, I haven’t. I have made disastrous decisions, mucked things up big time in so many ways that I’ve lost count. But that’s not the point. It’s always what you do with yet another inchoate draft, a seemingly irredeemable art journal page, and a major bad decision that gets you closer to where you see yourself headed, if you’re willing to work a little more with it, and then give the mistakes over to imagination and grace. Over and over again.

This is creativity’s essence: the vision to see through failure after failure, blunder after blunder, and let the beauty emerge.

Creativity isn’t economical. Creativity’s full of thousands of pages of wasted words, journal pages decorated in expensive mediums and then covered up by gesso, in the need to start over again. Creativity’s full of excess, as Blake understood, an excess that is as necessary to our creative life as air and water are to our physical life. Formula only takes us so far. This is what religious dogma doesn’t understand, and where science fails when it demands unremitting skepticism. The artist’s adventure, and life’s adventure, is in breaking from the formulas into failure and perseverance.

We may touch mystery in the process, learn more than we ever imagined possible for ourselves.

This morning, I remembered my beloved Giotto art book on the bottom shelf in my living room in Cambridge. It was such an indulgence when I bought it, but I had to have it. The closeups, the thick black lines, the vibrant pinks and blues and greens, the brilliance and passion and tenderness with which Giotto painted. I then remembered my first visit to D. C., and my visit to The National Gallery. I turned the corner, and there was my first Giotto. I didn’t know The National Gallery had a Giotto, but there it was, and I immediately knew it was a Giotto. There was no mistake, the way the infant grasped the Madonna’s hand, the unmistakable break from religious iconography into Renaissance humanism. I gasped, and almost cried. My first Giotto in person.

One day, I will visit Italy, and see the Giotto Saint Francis cycle, I will view his works around the churches in the Italian countryside. But this morning is not that morning. This morning, I took a book on Giotto that I found in a box of old books that inexplicably failed to make it to the shelves for a community book sale, and I lovingly tore out details from one of his great frescoes. I glued the fragments on an art journal page that I’ve been working on, glued them over an extravagance of metallic blues and Caran d’Ache pigments and various lines that I created with a French curve set, obliterating some fine work, so I could cut up Giotto and make his work my work. I gilded the page’s edges, and then I gilded the fragments. I thought how fortunate I am to be living this life, creating this art journal page, listening to the birds, and seeing the sunlight bathe the room.

I am the luckiest person that I know, to be able to document this experience in writing, an entry that could not be written had I not given up a life that was not worth hanging onto, while embracing the uncertainty of the one waiting.

In giving up the Giotto on the shelf, I got the one I could use.

It’s a good day, and I’ve come a long way.