“Annigonol ydy un iaith.” — One language is never enough.

Sometime in the late 90’s, I hiked from the Isle of Anglesey, through North Wales, Snowdonia, and down the Pembrokeshire Coast path, with the Irish Sea to my side. I explored miles of solitude and natural beauty and ancient relics and history, an experience that I will be expanding in an essay, for a planned collection.

For today, I offer the following to honor the Scottish independence referendum, for reasons that I hope will be clear by the entry’s end.

On the first leg of my Welsh journey, I stayed on Anglesey, a large island off the western shore, that’s a short ferry trip from Dublin, across the Irish Sea. The island is a remarkable land, as are its people. I stayed on a 550 acre farmhouse bed and breakfast, taking day trips from this rural, comfortable base. Mrs. Jane Brown ran the bed and breakfast, and she was a model of charm, hospitality, warmth, and a library of history about the area and Welsh lore. Mrs. Brown gave me the kind of oral history rich in color and texture that only a native could create.

Her generosity was singular. Mrs. Brown and her daughter-in-law took me on several day trips to places that few outsiders could have or would have known about. One trip was to a church used only few months a year, for when the tides change with the seasons, water surrounds the church the rest of year making the sanctuary inaccessible. There are no public programs to change this. Instead, the locals work with the way things are, they honor nature, this ancient space, and the mystery of the two together. The doors open and close at nature’s invitation. When the waters recede, it’s a local pilgrimage that honors life, death, and change. Archaic, I entered a world in which rituals from nearly a thousand of years ago remained unchanged, the rough old stones and worn wooden benches whisper stories that give themselves over for a brief time. Most of the year, this space protects itself from the outside world, with the rise of water around it.

The world I entered in North Wales, and particularly in Anglesey, was rare. Strangers were friends in minutes. I remember tea with Mrs. Brown, her daughter-in-law, and their distant relatives who lived in an old farmhouse, near the island’s border to the channel, and the Welsh mainland. Mrs. Brown’s distant cousin embraced me, a modern American woman, and introduced me to the entire family, including the horses and sheep, an introduction followed by warm elderberry pie fresh out of the oven, which was a large stone hearth in the kitchen, hot black tea, and lively conversation.

One does not pay for such human, “cultural,” experiences, they are freely given when people share of themselves.

But here’s the setpiece of these hastily shared anecdotes, and why I offer them today in regards to Scotland:

Mrs. Brown fixed me a lovely dinner before I left, that included her entire family, with whom I had become attached, in two weeks. Over dinner, they asked what I would be doing when I left, where I would go, what were my plans. I mentioned my stint to hike up Snowdonia, then I would bus over to the coast and begin my long hike down the length Pembrokeshire Coast path, eventually taking the train from Carmathen to London. “I’m excited about London, because of the free museums,” I said. They chuckled.

I then said, in light humor, “Maybe I’ll bump into the Prince of Wales,” believing that I was connecting my London visit with them, even though they would be miles away, trying to tell them that I would miss them, and be thinking of them, still.

The table went silent. I looked around, and suddenly the uncommon warmth that had been given to me disappeared, and there was a palpable void.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

Mrs. Browne, said curtly, “We don’t speak of him here as ‘The Prince of Wales.'”

“Okay. I’m sorry. But why?” I asked, completely perplexed. I had offended these folks who had been wonderful to me, had adopted a simple bed-and breakfast lodger as family during my time with them, and I hadn’t a clue about what I had done.

Then, raising her voice, as if to take a knife and change history in a single slash, “Because he’s not Welsh!”

Dumb American, I thought to myself, wondering how I could be so thick.

The tension dissipated, and we returned to Mrs. Brown’s lovely supper, and Mrs. Brown opened another bottle of Welsh made wine. But I then understood that there were things not usually talked about with guests, and I also understood how deep the Welsh identity cut here in the northern parts, in the farthest reaches from England’s geographical influence.

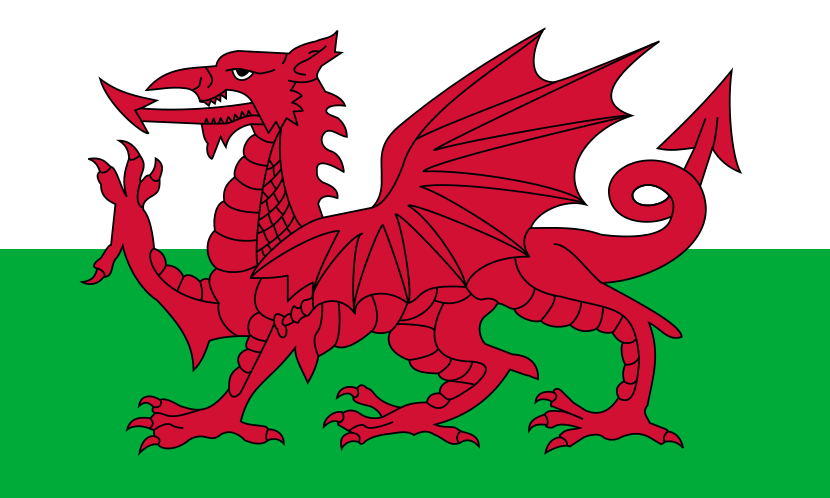

The history made privy to me was Welsh history. Not English history. Not the history of the United Kingdom. They were Welsh. They had unique stories, and a unique understanding of the world, that they kept alive, passing down, giving freely. The were Welsh and proud. This identity was perhaps nowhere more clear than in the signposts written in Cymraeg. The smaller the village, the less the need or want to translate. You understand or you don’t.

Mrs. Brown and her family will most likely never see an independent Wales. I’m guessing they are watching Scotland’s vote with deep personal pride, and a kinship with those who share an island with those who dictate a strained beast known as “The United Kingdom.”

“He’s not Welsh!” I’ll never forget that moment, a moment that changed my too American perspective, and made my blood identity to my Scottish kin deeper, gave me more circumspect respect for the spirit of those who refuse the control of anyone’s history, no matter how quiet that rebellion.

Now, when I say, “I am a Guthrie, ” and remember the stories my mother gave to me about her family’s people, and their independent pioneering into the midwest, I understand something a little deeper and richer, thanks to Mrs. Brown.