Hello friends,

Today many folks celebrate Mother’s Day.

This entry, however, is about Mothers’ Day.

I’m reflecting on three lines of thought, and perhaps these thought strands will give you something.

First strand:

I had a conversation yesterday with a dear friend who chooses to be child free. We talked about the happiness and freedom we experience as child free women, no regrets, perfect peace in the choice and how being child-free has happily played-out in our lives.

And I told her this: I never wanted to be a mother — there were windows in my life when a family and children seemed possible, when I was younger, but I always chose in the direction of my education and intellectual-creative development. Deep in my bones, in my knowing, raising children was never part of this life’s journey.

When I played with dolls as a child, I liked Barbie — sexist, perhaps, but she also held the ideas of autonomy, choice, and style. My Barbies had a big, lovely hand-me-down-house, given to me by a family friend. It wasn’t fancy, but in my imagination, it was a castle. And my Barbies had dresses, lots and lots of stylish dresses.

My grandmother’s handiwork perfected the art of Barbie dresses with scraps of old cloth and crochet hooks. When folks from church came over, they commented, “that’s the best dressed Barbie[s] I’ve ever seen.” The running church joke about the Barbie dresses complimented my grandmother’s impeccable craftsmanship, but it was also a fact.

Barbie had her own place, and she dressed to the nines,

Ken remained in his swim trunks, and was he ancillary in the fantasy narratives.

He appeared in the castle only to be with Barbie on her terms.

They had no children, and I never played at raising babies. Perhaps because the women I was raised with worked, I never observed infant or child care. Yes, I had baby dolls, but they were for sleeping, comfort talismans, not make-believe babies for whom I had to care, feed, and change.

No diapers for me, I had Barbie and her wardrobe. That’s what I liked, at least when it came to dolls.

***

Second strand:

Heather Cox Richardson’s re-post today that rightly recognizes how the idea of Motherhood is being politically twisted — quelle surprise — in these days. I invite you to read her Facebook post in its entirety here.

From her entry:

I told this story here two years ago, but I want to repeat it tonight, as the reality of women’s lives is being erased in favor of an image of women as mothers….

If you google the history of Mother’s Day, the internet will tell you that Mother’s Day began in 1908 when Anna Jarvis decided to honor her mother. But “Mothers’ Day”—with the apostrophe not in the singular spot, but in the plural—actually started in the 1870s, when the sheer enormity of the death caused by the Civil War and the Franco-Prussian War convinced American women that women must take control of politics from the men who had permitted such carnage. Mothers’ Day was not designed to encourage people to be nice to their mothers. It was part of women’s effort to gain power to change modern society.

The Civil War years taught naïve Americans what mass death meant in the modern era. Soldiers who had marched off to war with fantasies of heroism discovered that long-range weapons turned death into tortured anonymity. Men were trampled into blood-soaked mud, piled like cordwood in ditches, or transformed into emaciated corpses after dysentery drained their lives away.

The women who had watched their men march off to war were haunted by its results. They lost fathers, husbands, sons. The men who did come home were scarred in body and mind.

Cox Richardson shows why Mothers’ Day is a more powerful animal than Mother’s Day. The former is about the political and sovereign strength of women, the latter is a construct that demands gender specific ideas to buttress social norms that don’t do much for mothers, mothering, or living children. In the latter, mothers and mothering are mired in stereotypes, expectations, and subjugation.

***

Third strand:

My spiritual-imaginal explorations have led me to an evolving devotion to The Divine Mother, the one who births all creation.

More precisely, She’s called me to herself, again.

The Great Creatrix, the vast invisible darkness from which the Universe herself expands, unfolds, who dances through the whole of everything, including our small, ephemeral lives.

The enormity is stupefying, this Great Mother Of Everything.

For too long, our World Religions have been male centric, male dominated, male privileging.

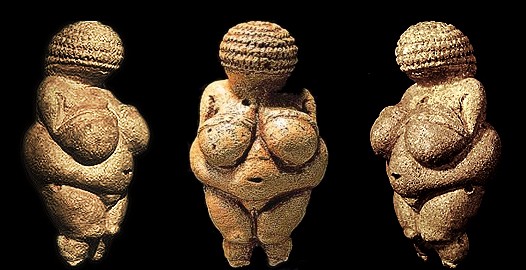

It wasn’t always so, the Great Goddess was our first original devotional object.

She was respected, honored, referenced, cherished, held in our hands as talismans to bring Her to our minds and hearts at every hour.

Our first dolls were the great Mother, figurines not to be cared for as dependent girls, but the One Source who cared for us, nurtured us, protected us, eroticized life on her terms:

Sloppy assertion? Do I have enough information to claim anything about any of these mysterious figurines, let alone the Willendorf? Self-serving rhetoric?

No more self-serving than the recently leaked SCOTUS draft, or any of the violence, domination, and anger on display in the name of ‘values.’

The wisdom and mystical traditions of these new patriarchal religions, all of them are new in comparison to the goddess, all the writings, saints, epiphanies, and revelations revealing the nature of Reality always understand that that the mystery beyond words is neither female nor male.

If anything, the mystics privilege the feminine, and nature’s generative, healing resilience as the means to living in our True Nature.

The Holy Spirit herself is an old Sophia artifact, the Mother meeting herself in the Immaculate Conception: the idea of human sovereignty written in female humility and devotion.

The evidence for such a radical recasting is in the texts and in the ancient practices, if we carefully clean the accumulated debris from the artifacts like spiritual archeologists, instead of rehashing old narratives and expecting a new result. Doing the same thing and expecting a different result is the definition of insanity, not personal or collective transformation.

But getting the Great Mother’s face back in our collective consciousness isn’t easy.

Men walk into rooms with their given-at-birth-collective permission slip, “made in the image of.”

Women have to wrestle their made-in-the-image-of from ‘the powers and principalities of this world” (Paul’s epistle to The Ephesians).

But another layer comes to light in one’s evolution when one recognizes that we really are from the dust — the earth, the Mother — and to dust we return.

We come from her, we go back to her.

Everything comes from her, everything returns to her.

We live on death. Our bodies are the bodies of stars, dinosaurs, animals, rocks, trees, flowers. Everything is connected, everything is recycled and life and death are illusions in the deepest sense. Life and death are constantly circling ouroboros style in this great cosmic life dance, that has never been ours, only Hers.

We’re at our most spiritually alienated when we believe we’re in this alone, and that the end-game in this life is eternal salvation or awakened enlightenment.

No, it’s just Her world, Her dance, Her work, and we’re here to hold Her hands and listen.

Everything is impermanent, so are we; and we just keep getting recycled, over and over.

Yet, we hold the wisdom, grace, pain, travail, beauty, resilience, and achievement of these ancient, recycled memories in our blood, bones, flesh.

It’s part of what it means to dance with Her, again.

There is One Mother, but in these memories, we all hold the memory of all mothers, no matter our gender, no matter our gender identity. We are all mothers in the Great Recycling Project. Mothers and mothering takes on a whole new life, and to know this Mother opens the door for collective transformation.

***

I told my friend another story, yesterday.

At one point in my life, I sponsored five kids through Christian Children’s Fund.

It’s probably not a choice I’d make today, but I made it then. I didn’t go to church, didn’t believe in the teachings, but CCF had excellent Charity Navigator ratings. I believe in tithing, and I support children’s development.

The kids received one hot meal a day, one multi-vitamin every day, and they were taught to read and write in their native languages. (Side note: it was devastating to me when the 9 year old Polish boy wrote letters more sophisticated and informative than the 10 year old boy from Alabama. There’s a lot more to say about this, but it’s for another time.)

This wasn’t the only charity I supported. But it was important to me. They were kids I felt a responsibility for, kids with names, faces, stories to tell. They wrote me letters, drew pictures, and my generosity helped them and their families.

“If everyone in America could support just one child,” I’d think to myself, “the world would be a better place.”

One day, out of the blue, after many years of giving, I received a letter from CCF with a honorary certificate of some type, and a letter.

I’d earned some kind of donor status, which wasn’t on my radar.

But this is what blew me away: over the course of my giving, I’d managed to donate over 36,000 dollars to support other women’s children, through one organization. This didn’t include any of the other organizations I felt committed to.

I’m not sure what that means. I’m going to take a guess here, though, and say that there is more than one way to be a good Mother, no matter your gender or your instincts.

I believe in One Mother, and all of her children. I believe that the stars, the sun, the galaxies, the flora, the fauna, the pebble, the mountain, the Republican the Democrat, the misogynist and the Wiccan, we are all, all of us, made in Her image.

We are Her. And for this reason, all is worthy of love, all is lovable, and all of us are Mothers.

Until next time.